Seven Amazing Facts About The Truth

What have online marketing, social media and paid-for digital propaganda done for our notion of the truth? As a philosophy and marketing graduate, the question has been bothering me for some time. I finally got around to do the research, so here we go.

The good news is that we are actually less likely to lie online. So, without further ado, Amazing Fact About The Truth (AFATT) number one is

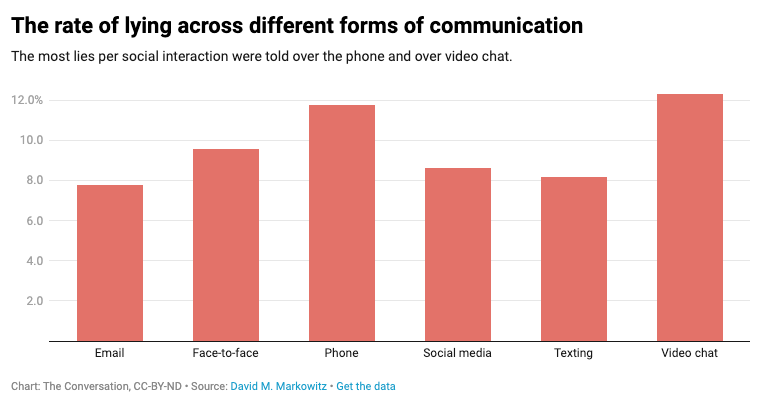

AFATT #1: People are less likely to lie online than face-to-face

Compared to face-to-face interactions, you won't throw in a casual lie or two quite as readily. This is in no small part due to the scrutiny you open yourself up to online. The most truthful medium of all? Email! (source: Markowitz, 2021).

The bad news is that we are less likely to detect digital lies. Our finely attuned bullshit detectors work much better in a face-to-face setting. This is not good, because even a handful of people deliberately manipulating digital truths can have a massive impact. In fact, according to Serota & Levine (2014),

AFATT #2: Some 5% of people generate over 50% of all lies!

So perhaps we should be asking a different question. Is social media enabling frequent liars? Vosoughi et al. (2018) studied exactly this question in the context of news. Their shocking findings? Lies spread faster than the truth! Read all about it in their paper, or in Sinan Aral's The Hype Machine.

AFATT #3: Digital lies spread faster than digital facts

Okay, now that we've established–to absolutely no-one's surprise–that the internet has a seedy underbelly, can we at least claim most of these lies are harmless? The white lies of omission that paint a brighter picture of your life on social media for example, those are harmless right?

This is a difficult question to answer. There is plenty of scientific and historical evidence that our tolerance for lies is culturally and socially shaped. And our cultural norms are shaped by our behaviour. For example, in Mann et al. (2014) they find that different social and cultural groups show different rates of lies of omissions and commission. As such we can say that,

AFATT #4: Our attitudes toward truth and lies are socially and culturally determined

If we piece AFATTs 2, 3 and 4 together, we could conclude the following: If our digital experiences are changing our living experiences, then we might be at risk of letting our wonderful natural bullshit detectors get numbed out by the 24/7 shouting match happening online. So these harmful little misrepresentations of the truth on social media and in other forms of digital communications might be having a snowball effect on our attitudes towards truth in general.

I don't know of any solid behavioural research linking our digital identity to our real-life identity. The most visible evidence of online-to-offline behaviour can perhaps be found in contemporary politics. There, our digital selves are often extreme cardboard versions of our physical selves. They are nevertheless aligned with the goals of our physical selves–or is it the other way round? ...

Let's leave the 'I WiFi therefore I am' question for what it is for the moment. On a personal level, truth is what we believe to be true. As such, truth is rooted firmly in our belief systems. The hardware of those belief systems is our memories (the software, language). And memory, as it turns out, has a bit of a reliability issue. Cited by Yingyi Han in his excellent overview of mediated memory literature published in Nature, Bernstein and Loftus (2009) summarise the issue as follows:

“[A]ll memory is false to some degree. Memory is inherently a reconstructive process, whereby we piece together the past to form a coherent narrative that becomes our autobiography” (Bernstein and Loftus, 2009, from Han, 2023)

If we take the inherent fallibility of our wetware at face value, personal truths become evolutionary. They are shaped by our surroundings and autobiographic narratives. The only external entity they pay fealty to is language (sorry, maths!). Should we choose to discard personal beliefs as a solid enough foundation for our common notion of truth, I can go all Nietzsche on the next AFATT and state that

AFATT #5: The currency of the digital world is trust, not truth

This is a consequence of how our digital platforms are set up. On social media, the past doesn't exist except in our presence. Its endless feeds present us with the all the digital reality we need. Digital relationships are one-to-many and many-to-many. In these types of relationships, truth–do I believe this person?–is less important than trust–do I trust this person with my time/money/reputation?

Remember our poor old bullshit detector, shaped by millions of years of evolution? It has evolved to tell us we can trust someone is telling us their true intentions. Intentions to share their food, or to not push us of a cliff at the first available opportunity. With the stakes so much lower in many-to-one and many-to-many digital interactions, Truth has been watered down to the related but less grandiose or old-fashioned notion of authenticity.

Does that mean our notion of 'truth' as we understand it has become irrelevant? Is there still something to be said for objectivity, science and evidence in common discourse? Is social proof evidence enough? I think there is still room for a notion of truth, as I will explain in the next AFATT:

AFATT #6: Truth indicates our level of confidence in a future state

As it happens, the future is the only truth in which we can still legitimately place belief in in the 21st century. So when we say "I believe it will rain in ten minutes", that is a truth we stand to live by (and we'll probably not head outside without a coat or an umbrella). Not a grand eternal edifice of The Truth in the Platonic sense, but a smaller, personal assertion about a future state of events.

This is what Dostoyevsky meant when he wrote that "truth is what remains". What has changed over time are the increments in which these remnants of our thoughts echo through reality. Whereas Plato was confident enough to claim eternal validity for his ideas, we often have no idea what the world will look like next week.

This perceived lack of stability is caused by the rapid pace of technological and social change in our environments. Unfortunately, our main weapon to combat this creeping sense of uncertainty is another technology–statistics. I fear our increasing reliance on data to ground our truths has made us myopic. The best predictions we make with statistical methods are in the near-term. A little further out into the future, anyone's guess is just as good.

For students of philosophy, this is a version the problem of induction, which is also a key problem in statistics and probability theory (cf. The Black Swan, MacKay, 2003). Statistical methods seek to ground predictions about future states in historical data. Like humans, they are only ever partially successful.

The strange thing — to me, at least — is that we are on the cusp of an age in which statistical methods will provide us with both the projections and the building blocks for our belief states. Machine learning models predicting future events processed by Large Language Models (LLMs) predicting the next token will give us the personal information contexts in which we formulate our personal truths. We will trust these models, because they sound more like us every day. As a result consensus, rather than being driven by discourse, will be shaped more and more by statistical aggregates generated by machine learning models. To this end, I want to leave you with one last AFATT:

AFATT #7: Unlike us, LLMs don't yet know when they are lying

At least for now, we have the dubious honour of beating LLMs in one key area: we humans are usually aware when we are deliberately manipulating the truth. To the best of my knowledge, there are no trained LLMs out there with an embodied self or a mature theory of mind (although I wouldn't bet money against several highly funded AI research groups working on exactly these topics). LLM hallucination is another one of those areas where AI researchers are still looking to make progress. So next time you interact with an LLM, be sure to check your natural bullshit detector before taking its output at face value.

Main sources

- Are people lying more since the rise of social media and smartphone? (2021)

- Everybody Else Is Doing It: Exploring Social Transmission of Lying Behavior (2014)

- The spread of true and false news online (2018)

- Evolution of mediated memory in the digital age: tracing its path from the 1950s to 2010s (2023)

- TruthfulQA: Measuring How Models Mimic Human Falsehoods (2022)